A dynamic whereby different acts of violence are superimposed on women’s migration processes. At this intersection, the gender variable is considered in relation to other variables: ethnicity, race or their condition as migrant women, leading to the existence of further violations and further forms of violence.

Introduction

A global consensus has emerged as to the interrelationship between forced mobility and gender in many ways. Migration has an impact on gender relations, either by reinforcing, challenging or transforming inequalities or traditional roles.

“Invisibilised. Migrant Women at Border Crossovers), shows how gender intersects and influences migratory experiences and highlights the violence that women face from origin, during transit, at borders and at destination. It concludes with a series of recommendations using a gender and rights-based approach, which we submit to governments and administrations, urging the co-responsibility of European and Spanish State policies in the violation of fundamental rights and the perpetuation of violence that annually leads to thousands of people’s lives being lost.

Glossary

Forced migration

This refers both to people who are obliged to migrate due to their country of origin’s unstable economic situation, and to situations of generalised violence or persecution.

Migrant women

This is used in the Origin and Transit chapters as it is associated with movement.

Migrated women

This is used in the Destination chapter to refer to women who, for different reasons, show some degree of socio-economic stability.

Migrants in need of protection

This is a category that UNHCR has included since 2018 – although its name has undergone changes – under the definition of those who were forced to flee their country and are in need of protection, especially from forced return and basic services, but which UNHCR does not consider as falling into any other category. Hereafter, in this report, we shall refer to refugees, understanding this to mean refugees in need of protection.

Traditional gender roles

Behavioural practices learned within a social group, fostering patterns of behaviour that perpetuate unequal relationships between what is considered “female” and “male”.

Gender-based violence against women

Insofar as it is the term used by the main international institutions in matters of gender equality, it will also be used throughout the report.

Continuum of violence

The concept of continuum of violence against women acquires a special meaning in the context of mobility, as it brings to light the fact that all the ways in which violence is expressed in the lives of women and girls follow the logic of temporal and spatial continuity. Gender-based violence against women is a global phenomenon, replicated in all cultures, regardless of religion, economic status or origin (although it may have different consequences). Women experience it throughout their lives and it may occur in any territory and place, both public and private, where there exist unequal gender power relations. In the case of women in migratory processes, different types and dimensions of violence accompany them wherever they go. Not just because they are women, but also because they are migrants, so they face overlapping violence in the contexts of origin, transit, destination and return. In turn, structural violence associated with discrimination and lack of access to rights, and migration policies that prioritise a focus on national security over protecting lives, make them even more vulnerable and perpetuate direct violence throughout the entire migration route.

Violence against women

The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) of the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) adopts the expression “gender-based violence against women” as a term that highlights how gender relates to the causes and effects of violence against women, both in the private and public domains, and to strengthen “the notion of violence as a society-wide problem, rather than an individual one, which requires comprehensive solutions beyond responses to specific events, perpetrators, victims and survivors”.

The intersectionality among different factors, such as the interrelationship between forced mobility and gender, is recognised by CEDAW in its Recommendation 35: “Gender-based violence against women is affected and often exacerbated by cultural, economic, ideological, technological, political, religious, social and environmental factors, as evidenced, among other things, in the contexts of displacement, migration”.

Consult the main categories and acts of gender-based violence against women

Such violence does not fall into separate categories, quite the contrary. Its boundaries are almost invisible, and they feed off one another. Insofar as these acts are not isolated events, but systematic behaviours, such practices have been acknowledged as human rights violations by different international and regional instruments and, accordingly, States are obliged to act not only to prosecute and try the crimes, but also to prevent and punish them.

- Physical violence: actions that cause physical harm or suffering and affect women’s wellbeing. The most extreme expression is femicide/feminicide which refers to the violent killing of women for reasons of gender, whether it occurs in the private sphere, in the community, or is perpetrated or tolerated by the State and its agents, by action or omission.

- Psychological violence: actions or behaviour that result in women’s degradation or suffering, through intimidation, threats, harassment, humiliation, bullying or behavioural control, among others.

- Sexual violence: acts of a sexual nature committed against another person’s will, regardless of whether the person has not given consent or is incapable of giving consent because he or she is a minor, mentally disabled or severely intoxicated by alcohol or drugs.

- Physical, psychological and sexual violence committed within the private sphere: including battering, sexual abuse of girls in the home, dowry-related violence, marital rape, female genital mutilation, child marriage, forced pregnancy, honour killings and other traditional practices harmful to women, violence perpetrated by other family members, and violence related to exploitation.

- Physical, sexual and psychological violence perpetrated within the community at large, including rape, sexual abuse, sexual harassment and intimidation at work, in educational institutions and elsewhere, trafficking in women and forced prostitution.

- Economic violence: achieving or attempting to secure another person’s financial dependence by holding total control over their financial resources, preventing access to them, including but not limited to prohibiting them from working or attending school.

- Institutional violence: violence carried out or condoned by the State, including the failure to fulfil its responsibility to guarantee access to rights without discrimination.

- Direct violence: this is the most obvious. It has a perpetrator and a victim, is usually physical or verbal and causes direct harm.

- Structural violence: this is the discrimination, unequal opportunities and unequal access to rights perpetuated by a system which, in turn, makes women more vulnerable to direct violence. It can be seen in wage gaps, in access to education or health for men and women, in the impunity of gender-based violence against women, or in the limited participation of women in public life, among others.

- Cultural violence: this is used to legitimise direct or structural violence and has an impact on the acceptance and normalisation of violence in societies.

Physical · Psychological · Sexual · Institutional · Economic ·

Physical · Psychological · Sexual · Institutional · Economic ·

Physical · Psychological · Sexual · Institutional · Economic ·

Physical · Psychological · Sexual · Institutional · Economic ·

Physical · Psychological · Sexual · Institutional · Economic ·

Physical · Psychological · Sexual · Institutional · Economic ·

The figures

Year after year, forced mobility is increasing. According to UNHCR estimates, 40 million refugees, asylum seekers and persons in need of protection were recorded in 2022.

The international migrant population has doubled in 30 years

According to UN data, between 1990 and 2020 the international displaced and migrant population has almost doubled, from 153 million to 280 million people living outside their country of origin.

146 million women were living outside their countries of origin, of which almost 20 million were under the age of 20, 96 million were between the ages of 20 and 65 and just over 19 million were over the age of 65.

Despite the acknowledged lack of information and data on women’s and girls’ migration, recent decades have shown changes in migration patterns, especially in four respects:

- Women’s migration is growing at a faster rate than that of men.

- More and more women are travelling independently, in contrast to those who travel following family members or partners.

- A new, sexualised international division of labour has emerged. Migrant women are increasingly in demand for employment in traditionally low-paid sectors, in casual employment, and with sub-optimal working conditions.

- Migrant women are active participants and a key part of the “global care chain”, which alleviates the worldwide crisis in caregiving.

280

The international migrant population has doubled in the last 30 years.

146

49% of migrants are women and out of these women, 20 million are minors.

96

Among women migrants, we should highlight the high number of women aged between 20 and 65.

40

Refugees, asylum seekers and people in need of protection in 2022.

51

Refugees, people seeking asylum or in need of protection are women, 21% of them.

Origin

It is essential for the gender perspective to occupy a central place in any analysis of migration‘s causes and consequences.

The voices of different women raise awareness and expose the endless vulnerations, abuses, struggles and obstacles that arise from the start of a migratory experience, affected from the outset by traditional gender roles.

In order to understand the complexity of human mobility, it is essential for a gender perspective to lie at the heart of analyses into the causes and consequences of migration.

Las historias de las mujeres que dan forma a este capítulo reflejan los contextos que causan la salida de sus países.

1.200

7.4

22

IN THE SAHEL REGION AND WEST AFRICAN COUNTRIES, SEXUAL VIOLENCE, ABUSE AND EXPLOITATION, HARMFUL TRADITIONAL PRACTICES SUCH AS FEMALE GENITAL MUTILATION, EARLY AND FORCED MARRIAGE AND HUMAN TRAFFICKING ARE COMMONPLACE.

West and Central Africa

THERE IS NO SINGLE CAUSE OF DISPLACEMENT IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA’S MIGRATORY FLOWS.

With a population of over 1.2 billion, Sub-Saharan Africa is rich in biodiversity and natural and mineral resources, but it has been brutally impacted by the effects of climate change, such as increased food insecurity, droughts and other extreme weather events, which exacerbate already-difficult living conditions.

In 2022 alone, natural disasters in the region caused 7.4 million displacements. This is three times the previous year’s figure.

OF THE 48 COUNTRIES THAT MAKE UP SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA, 22 ARE CONSIDERED FRAGILE OR ARE AFFECTED BY CONFLICTS.

The complex interaction between conflicts, climate change, food insecurity, lack of socio-economic opportunities, inequality and gender-based violence against women is causing women to move not only to neighbouring countries, but also across interregional and intercontinental borders in search of a future. With overlapping crises, women are more exposed to risks and insecurities because they have fewer means to seek alternatives and gain access to livelihoods. Despite this, they continue to take on family and domestic responsibilities.

In conflict and post-conflict situations, women, girls and boys suffer the most, as violence against women worsens and escalates. Women’s bodies are used as weapons of war. So much so that gender-based violence against women in conflict contexts has been recognised as a human security issue.

Although women represent more than half of the population in Sub-Saharan Africa, they are excluded from issues and decisions that affect their lives and they face numerous gender-based discriminations that violate their fundamental rights. Limited access to opportunities for economic and political participation, education, health care and justice, among others, contribute to the feminisation of poverty, illiteracy and vulnerability.

Witness accounts

Central America

THE MIGRATORY REALITY OF NORTHERN CENTRAL AMERICA IS MARKED BY POLITICAL, GENERALISED VIOLENCE, SOCIO-ENVIRONMENTAL AND HUMAN RIGHTS CRISES.

It is also a consequence of the exhaustion of economic models that concentrate wealth and deplete natural resources. All these factors influence many of the migratory decisions taken in a region where over 8 million people, or 25% of the population, have humanitarian needs.

ADDED TO THIS REALITY AT ORIGIN IS THE DIFFERENTIATED IMPACT ON WOMEN AND SPECIFIC GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE.

People working in the informal sector are the most likely to take the migratory route, both for economic reasons and because they are one of the groups targeted for extortion by gangs. If we break down the region’s economic data by gender, we can state that women are the most affected by the factors driving forced migration in the economic sphere.

The context of violence in Central America’s northern region is a scenario that forces people to take the decision to migrate. Many of the migrant men and women from Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras have experienced violence in their communities of origin due to criminal organisations, which in many cases, thanks to the consent of the authorities, enforce tight territorial control through forced recruitment, extortion, threats, aggression, and murders. It is not uncommon for women and men to take on different roles; women are useful resources for the most dangerous activities, bodies that can be taken by force, or as territories for settling differences and vendettas among rivals. Against this background, we therefore also refer to women’s bodies as weapons of war.

Furthermore, Latin America remains the most dangerous region in the world for environmental and territorial defenders, with 88% of the world’s recorded killings in 2022. Women defenders are also exposed to many other forms of gender-specific violence, from sexual assault to rejection by their families and communities. Violence impacts women differently. In some countries, femicide rates have reached epidemic levels. The highest number of cases of gender-based violence against women occur in the domestic sphere, and the rate of teenage pregnancy is an alarming sign of violence among this population group.

In most cases of gender-based violence against women, the state is unwilling or unable to provide protection. Without elaborating on aggressions by State authorities, nor on the involvement of security forces with criminal actors in the region’s territories, it suffices to consider the high rates of impunity and lack of access to justice for violent gender-based crimes against women. Impunity and lack of trust is one of the driving forces behind decisions to migrate.

Structural causes that are forcing people in the region to migrate: 1. Unequal opportunities, 2. Lack of trust in democratic processes, 3. Deficient tax and social protection systems, 4. The influence of drug and arms trafficking, 5. Insecurity, militarisation and violation of human rights, 6. Vulnerability to climate change and variability and 7. An individualistic outlook on life.

Company of Jesus, Mexican and Central American Provinces, 2022

8

60

88%

Witness Accounts

Transit

The Continuum of violence along the routes and at borders

BORDERS

BORDERS

BORDERS

BORDERS

BORDERS

BORDERS

BORDERS

BORDERS

BORDERS

BORDERS

THE CONFLICT BETWEEN HUMAN RIGHTS AND MIGRATION CONTROL COULD NOT BE CLEARER: MIGRANTS ARE SUPPOSED TO BE DETERRED FROM CROSSING A BORDER BECAUSE THEY MIGHT DIE. IT IS IMPOSSIBLE TO PROTECT THE RIGHT TO LIFE WHILE SIMULTANEOUSLY ATTEMPTING TO DETER ENTRY BY ENDANGERING LIFE.

Report of the Special Rapporteur of the Human Rights Council on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions: Unlawful death of refugees and migrants

Expresiones comunes a las políticas de contención de flujos migratorios

Securitisation and militarisation approaches

Containment and national security-focused policies are often based on deploying physical barriers and advanced surveillance and deterrence equipment at borders, operated by public or private security forces. This approach turns migrants into objects of surveillance and can have a dehumanising effect, leading to greater acceptance of collective measures against them on the grounds that they represent a ‘threat’ to sovereignty and national security. One example is the complaints regarding Frontex’s involvement and use in facilitating cases of illegal refoulement at the Turkish and Greek maritime borders. The “big surveillance machine of the Mediterranean” has a policing approach that is devoid of a human rights perspective and lacks transparency.

Externalising borders

This refers to policies aimed at ensuring that “border control does not take place at physical borders”, so as to prevent people from ever reaching the country of destination and to keep them from seeking protection. The most visible version is interception both on the high seas and on land, or the funding of migration control in third countries to ensure that refugees or migrants return to their countries of origin or remain trapped in transit countries. The requirement is usually for greater control of human mobility not only in border areas, but throughout their territory, thereby transforming them into “border countries“, or what other authors call “vertical borders”. Morocco and Mexico are two examples of this process in relation to Spain and the EU and the US respectively.

As a result, borders have been expanding and shifting symbolically and geographically. They are no longer located within the territorial limits of the destination areas but encompass increasingly larger territories in which migration control policies promoted and financed by the EU or the US are implemented. Spain has played a major role in these policies with regard to Africa, both with Morocco and with sub-Saharan countries. One unprecedented expression is what Spain established with the so-called “operational border concept” in Ceuta and Melilla, aiming to move and reduce Spanish jurisdiction for the purposes of migration management and asylum, not to the actual border line, but until the people had passed the police line attempting to contain their passage beyond the border line. In other words, acting as if the persons were not yet in Spain. It is obvious, and this has been established in European case law, that overcoming the border obstacles located on Spanish soil implies prior border crossing.

Meanwhile, the United States has bolstered funding, measures and agreements with Mexico and Central American countries for control and surveillance, and has also implemented different policies for externalising international protection and migration management, such as the current Secure Mobility Programme, which has set up migration processing and international protection centres in Colombia, Costa Rica and Guatemala.

Pushback

This refers to the various measures adopted by states, sometimes involving third countries or non-state actors, which result in migrants being summarily forced to return to a country or territory, or to the sea where they have attempted to cross an international border, or have crossed it, without an individual assessment of their human rights protection needs.

The Special Rapporteur on Migrants’ Rights has been categorical in stating that this practice denies migrants their fundamental rights by depriving them of access to protection under international and national law (right to non-refoulement), as well as procedural guarantees. Furthermore, it broadens the definition to also cover measures and practices that deny migrants access to the territory or jurisdiction of a State, prevent their disembarkation, or hinder the continuation of their journey, as it considers effective access to the territory to be an essential condition for exercising the right to seek asylum. In his report, the Rapporteur mentions the example of expulsions by Spanish authorities of migrant populations to Morocco under the 1992 bilateral readmission agreement and the 2015 law that allows for “border rejections” of foreign nationals attempting to enter Spain irregularly from Morocco. The judgments of the European Court of Human Rights and the Constitutional Court, even with their multiple contradictions or lack of clarity, do not take their legality for granted, or at least identify which practices are illegal and which could be legal if the guarantees are respected.

The migration policies and dissuasive measures agreed between the EU and North African countries, and between the US and Mexico, have turned Europe into a fortress where the African population is unwelcome, and the region of Central America and Mexico into a laboratory of practices and policies.

Along the route, women, men, families and minors have to overcome geographical barriers and walls, whether constructed, human, technological, legal or illegal.

Transit is an invisibilised and increasingly dangerous stage as a consequence of border externalising policies, leading to an increase in unprotected irregular routes, in an inherently unsafe context. Women face specific gender-based violence, in addition to the violence that, in many cases, caused them to leave their country of origin, and to the violence suffered by the whole population in transit.

The separate descriptions of violence do not mean that they are incompatible with each other; in fact, the vast majority of the time they occur simultaneously and intersect. This concurrence is also fostered by the multiplicity of perpetrators and locations. Such forms of violence occur along the route, at borders, in shared flats or rooms, in camps, jungles, forests and deserts, in workplaces, or on city streets, among others; and they occur both at an interpersonal and a social level – committed by fellow travellers, men from other countries, “smugglers” or coyotes – and at an institutional level, perpetrated by police or security forces and other public authorities and tolerated by the state.

WITNESS ACCOUNTS:

Transit through West Africa and Morocco towards Europe

The European fortress

The Mediterranean Sea has turned into a blue graveyard, the Sahara Desert into an open-air cemetery and the countries of the North African coast into impenetrable walls.

UNHCR Special Envoy for the Western and Central Mediterranean Situation

73% of migrants from West Africa and the Sahel remain in countries of the same region.

Nevertheless, migration policies and deterrence measures agreed between the EU and North African countries have turned Europe into a fortress.

THE EUROPEAN FORTRESS

THE EUROPEAN FORTRESS

THE EUROPEAN FORTRESS

THE EUROPEAN FORTRESS

THE EUROPEAN FORTRESS

The journey towards Morocco

The situation of urgency and vulnerability that women find themselves in before beginning a migratory journey often leads them to start without prior planning and in a context of misinformation and deceit that is exploited by trafficking networks, smugglers and other organised individuals who seek to profit from others’ suffering. The mere reality of being a woman, the violence they face, family pressure, the responsibility of care and motherhood, among others, all influence their decision, and also condition the future of their migratory journey.

Insofar as the vast majority of African countries require a visa to enter Europe, many of the migratory routes that start in West African countries converge in Morocco. There are as many migratory processes as there are people, and the routes – air or land – depend on country of origin.

Factors that increase the risk of falling victim to trafficking

Since trafficking is one of the most devastating situations of gender-based violence against women, it is worth analysing the factors that increase its risk, as examples of the different overlapping and intersecting forms of violence against women:

Climate change and armed conflict

Climate change or conflicts between countries are increasing the risk of women and girls falling victim to trafficking. These crises intensify women’s and girls’ vulnerability (poverty, economic insecurity, displacement, violence against women and discrimination).

Access to education

Unequal access to education contributes to the trafficking of girls and young women ( it allows them to generate income for their families).

Gender-based violence

25% of trafficking survivors experienced multiple forms of gender-based violence prior to being trafficked. Acceptance and justification of violence against women are key factors in the vulnerability of trafficked women.

Migratory policies

Labour and migration laws do not take human rights and gender perspectives into account. Women are increasingly likely to seek employment in unregulated sectors.

THIS VIOLENCE IS SO PERVASIVE THAT MANY WOMEN ACCEPT SEXUAL VIOLENCE IN TRANSIT AS A PRICE TO PAY IN ORDER TO KEEP MOVING FORWARD.

Within this region, border crossing between countries is not restricted. However, freedom of movement is not synonymous with safety. In fact, travel is inherently dangerous. On the one hand, as a consequence of political instability and active conflicts in the Sahel, crossing the borders of countries such as Niger, Mali, Burkina Faso and Nigeria involves a risk and greater insecurity. On the other hand, land routes from West Africa entail crossing the Sahara Desert, and in the conditions of vulnerability that migrants do so, this implies a long journey, facing very serious risks.

This route is without doubt dangerous and affects all people. However, the conditions of vulnerability, travelling along remote roads to avoid detection, riding in overloaded vehicles, trusting traffickers or smugglers, affect women and girls differently, and in addition to rights violations, they also face specific gender-based violence. They are exposed to robbery, extortion, kidnapping, physical and psychological violence and sexual abuse by traffickers, the populations of transit countries, fellow travellers or border agents.

WITNESS ACCOUNTS

Morocco and the border

Europe's gendarme

Externalising policies for the border between Spain and Morocco, with the complicity of the EU, make this African country a required destination, or a place of transit for a longer period of time than expected. Due to its proximity to Melilla and Ceuta, the sub-Saharan population that succeeds in reaching the cities of Nador and Tangier does so mainly with the aim of crossing into Europe.

In 2023, there are 10,225 refugees and 8,908 asylum seekers living in Morocco.

These figures are nearly double the 2020 figures and do not give the full picture, as they only represent the regularised population and conceal the reality of thousands of people from West and Central Africa living – or rather surviving – in the country.

Since the border fences were put up in 1993, bilateral relations and agreements for migration control between Spain and Morocco have continued uninterrupted. These policies generate repression, violence, discrimination and cause the death and disappearance of hundreds of sub-Saharan Africans.

Witness accounts

Despite the different dynamics arising in the different cities, they are all defined by systematic violence and human rights violations. Border externalising and containment policies extend the stay of sub-Saharan Africans in the country in inhumane conditions. Migrants, and women in particular, face racist and xenophobic discrimination that affects their ability to exercise their economic, social and cultural rights (ESCR), such as access to housing, health, employment and schooling.

Nador

In Nador, apart from the policies implemented in recent decades, the measures put in place during COVID-19 and after the Melilla massacre of 24 June 2022 have significantly affected life in the city.

Both events have led to an intensification of economic, political and social instability and a harsher repression of sub-Saharan Africans. As a result, the stay in Nador is often not very long and many people seek refuge from police controls in camps built in the forests of Mount Gourougou, and in other areas surrounding the city. Despite attempts to get away from the hostility of the city, almost daily, the police carry out violent raids involving the theft of phones, money, passports; the burning of camps and sexual violence against women; arrests and deportations to the interior of the country.

Tangier

As it is further away from the border, police repression is slightly more limited and, especially for women, it is easier to find employment opportunities in the domestic sector, although in very insecure conditions. However, administrative restrictions on obtaining a carte de séjour – a residence permit – hamper the possibilities of accessing the regularised labour market and put many women in situations of vulnerability and violence. As a result, many admit to begging –taper salam– as a source of income to cover basic food and accommodation expenses. Living on the street exposes them to violence and discrimination by the Moroccan population and increases the likelihood of being detained and deported.

Casablanca and Marrakesh

Increased repression and the tightening of border control measures on the northern coast has prompted the activation of new irregular migratory routes and displacements within the country in search of alternative opportunities. Consequently, after months of struggling to survive the hardships of the cities near the borders, when they need to look after themselves, protect themselves or work to earn money, the sub-Saharan population, men and women, move to inland cities such as Casablanca or Marrakesh, respectively, where they say that living conditions are “less challenging”. The level of difficulty is largely relative because, as a protection or defence mechanism, it is common to normalise violence and violations of rights and to take comfort in the notion that “there are worse places”.

Oujda

There is a growing trend of sub-Saharan Africans moving towards Oujda, a city in eastern Morocco, seeking to cross Algeria to reach Tunisia, where they believe it is cheaper to reach the Italian coast. In response to this new trend, the EU has already reacted and continues to focus on containing migration and delegating border control to third countries. Accordingly, by signing a Memorandum of Understanding in July 2023, the EU has pledged to provide economic and technical support to Tunisia to discourage migration to Europe and block safe and legal routes.

Laayoune, Tan-Tan and Dakhla

Tan-Tan or Dakhla, and even from Mauritania or Senegal, to the Canary Islands. This route is extremely dangerous owing to its length, the strong tides and the scarcity of search and rescue operations. All this makes it the deadliest. In fact, 1,784 people died or disappeared in 2022 alone (Caminando Fronteras, 2022), although it is estimated that these figures do not represent the full picture. The Atlantic Route’s activation has led to sub-Saharan Africans to relocate to cities on the west coast where they either wait for the opportunity to cross or work to make savings in order to pay for the journey.

The role that Morocco is playing as Europe's gendarme also violates the right of access to international protection both in Morocco and in Spain. Many people are potential beneficiaries, yet they encounter numerous obstacles that prevent them from undertaking the procedures.

On the one hand, UNHCR in Morocco manages applications for international protection from its office in Rabat and there are no offices in the cities or at border points. Therefore, despite the difficult living conditions in the country, those who choose to apply for international protection have to travel to Rabat, taking on the economic cost and the risks that this journey entails. Additionally, even those who have initiated the procedure and are awaiting a decision as to their asylum say they are unprotected, since they receive little assistance and continue to face raids, arrests and deportations to the interior of the country.

The deportations “are legal in the country except in the case of women with minors, pregnant women and asylum seekers, but the Moroccan police do not respect these exceptions […] they arrest sub-Saharan people regardless of whether they are men, women, pregnant women or women accompanied by minors, asylum seekers…”

Extract from an interview given during the journey to Morocco

On the other hand, despite the fact that Article 38 of Law 12/2009, regulating the right to asylum and subsidiary protection in Spain, recognises the possibility of applying for international protection at Spanish Embassies and Consulates, the reality is that no government has approved its regulatory development and access to the asylum procedure through this channel is systematically prevented.

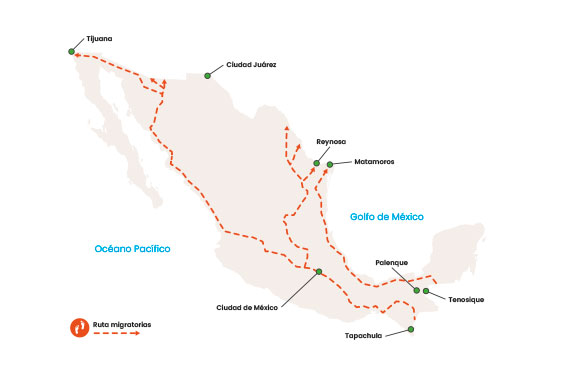

Transit through Central America and Mexico towards the United States

The years following the pandemic saw some of the most complex and rapidly evolving dynamics in the Central America-North America region. Migration from the northern countries of Central America (El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras) has been joined by unprecedented numbers of migrants arriving by land in Mexico, crossing through Central America from Venezuela, Cuba, Nicaragua, Colombia, Ecuador, Haiti, or even from countries in Africa, Asia, and Europe.

Throughout this journey, migrants are confronted with a permanent vertical border, i.e. they have to overcome a kind of obstacle course of physical, geographical, legal, social and cultural barriers, which particularly affect women.

In 2022 there were more than 1,000 deaths and disappearances in the region, due to a variety of causes, including drowning, accidents involving dangerous transport, extreme environmental conditions, lack of adequate shelter, food and water.

THE VERTICAL BORDER

THE VERTICAL BORDER

THE VERTICAL BORDER

THE VERTICAL BORDER

THE VERTICAL BORDER

The journey towards México

The so-called "Darien Gap", a tropical rainforest covering over 5,000 square kilometres separating Colombia from Panama, has seen a surge in the flow of people, especially since 2021.

Once migrants manage to survive and pass the Darien Gap, they come up against hybrid public-private systems of movement through Central American countries until they reach the border of Guatemala with Mexico, usually by paying private buses for the transfer, which often increase or double the cost of the ticket, and are controlled and run by the security forces of the country they are in. The economic factor is precisely one of the barriers encountered on this stretch of road. Other obstacles that make the journey difficult or force them to stay temporarily are legal issues, such as the visa requirements in a number of South American countries.

WITNESS ACCOUNTS

Reaching and crossing Mexico

United States' “guard dog”

The main concerns regarding the situation of migrants during their journey through Mexico are the process of militarising migration policy, state persecution and violence caused by organised crime, and institutional violence affected by the lack of real protection measures.

Those who stay at the southern border for a time, sometimes to save money, because they have applied for a humanitarian visa or asylum, or because they have decided to stay until their chances of reaching “the North” improve, find themselves in cities with poor living conditions, which sometimes come to a standstill, with minimal efforts towards integration and even less of a gender-based approach.

One of the indicators that Mexico has also become a forced destination country is the increase in asylum applications in recent years – more than 100,000 per year since 2021. This contrasts with the arbitrariness of the asylum system. Currently, in the absence of a standardised procedure in practice in the country, each territory implements different mechanisms in a discretionary manner that prolongs the process. Furthermore, discretionality is also found in protection decisions, depending on the nationality of the asylum seeker – applications from people from Venezuela are interpreted differently to those from Guatemala, for example – or according to a certain type of violence. In this last regard, in practice, some organisations complain that it is difficult to grant asylum for gender-based violence.

Us BORDER with MEXICO

Us BORDER with MEXICO

Us BORDER with MEXICO

Us BORDER with MEXICO

Us BORDER with MEXICO

US border with Mexico

The US border with Mexico is more than 3,000 kilometres long, of which approximately 1,000 kilometres correspond to walls or fences, which are complemented by other natural barriers (deserts and rivers), and human and technological obstacles, through deployments by the Border Patrol (CBP) and other security forces.

It is considered one of the most dangerous land borders in the world.

Border cities are inaccessible to people arriving from abroad, who usually have to settle in informal camps, shelters or rent on the outskirts because they are cheaper. These areas have no public services and are very poor, which especially affects women and mothers. Cities such as Tijuana or Ciudad Juárez have a network of shelters, but organisations do not define it as a welcoming system, because according to Alejandra Contreras (SJR Ciudad Juárez), “the shelters do not have the capacity to hold people for long periods of time, which causes a problem stemming from migration policies, which have turned it into a detention city”.

There are only 3 ways to request asylum at the US-Mexico border:

Request an appointment through the CBP One mobile app for asylum applications. Successfully passing this appointment – where the CBP asks general questions about the reason for departure – does not mean formal entry clearance, but it does imply the possibility of entry to apply for asylum. A limited number of appointments are available.

01

Joining waiting lists or physical queues to get a slot for entry past the gate to apply for asylum, without having made an appointment on the CBP One application. These queues are not regulated, they are usually organised at a local level. Besides the initial interview, you have to justify why you have not requested an appointment. There is a chance of being temporarily detained during the process, especially for single persons of legal age.

02

Going through unofficial crossing points and turning oneself in to the authorities in the US to apply for asylum. The much stricter “well-founded fear” interview is applied directly; if the interview is not passed, the expedited deportation process is triggered; there is a greater chance of being temporarily detained if the interview is passed.

03

Destination

THE ARRIVAL, BUT NOT “THE DESTINATION”

Arrival to the Spanish State

The polarised thinking that characterises Western culture divides reality into opposing pairs that perpetuate unequal power relations: male-female, public-private, reason-emotion, culture-nature, north-south, etc. By the same logic:

The population is divided between native people and “migrant” people or between regular people and people in an irregular administrative situation.

This way of understanding the world has shaped the organisation and behaviour of Western society, where the racist heteropatriarchal system governs, generating dynamics of discrimination on the basis of sex, gender, race, ethnicity or social class, among others.

This dichotomous reasoning allows us to reduce the arrivals of foreigners to the Spanish state into regular and irregular. The Spanish state and the EU argue that they are acting fairly. However, the problem lies in the reluctance to delve deeper into the reasons why the number of people leaving their countries increases every year; to identify the reasons why these people are unable to gain regular access to Spanish territory; or to acknowledge who is responsible for the violations of rights, disappearances and deaths.

Access to International Protection

Spanish legislation on international protection provides two types of procedure to apply for International Protection

- At the border, which is carried out in border environments or in CIEs (Immigration Detention Centres),

- On Spanish territory at Asylum and Refuge Offices or police premises.

Are borders not Spanish territory?

The way we think and construct reality is influenced by narratives, i.e. how we express ourselves. Differentiating procedures between the border and Spanish territory gives us the intuition that migration policies are prioritising the control of Fortress Europe over protection and the right to life.

The procedure within the territory is not easy, especially when it concerns persons of non-European origin, and is currently practically impossible. For two years now, access to appointments has been congested and blocked. In addition to this obstacle, there is the vaguer barrier of misinformation. Those who manage to begin procedures face a complex, painful procedure, as these are people who are fleeing their countries for reasons that endanger their lives and integrity. However, rather than trying to make up for these difficulties, the asylum application process is arbitrary, deeply intrusive, revictimising and confusing.

«Disinformation does a lot of harm: it prevents people from accessing international protection procedures out of fear, or they access them without legal advice or adequate accompaniment, which are crucial for prior preparation; or they give up because they cannot get an appointment».

SJM Spain Legal Team

The trend of border externalisation policies is worrying, and in particular, the orientation of the EU Pact on Migration and Asylum.

These characteristics grow more intense in border procedures, because the acceleration, time and place where the procedure is carried out cause a deterioration of procedural guarantees that directly affects the chances of acknowledgement. In this respect, we are concerned about the trend of externalising border policies, and in particular, the approach of the European Pact on Migration and Asylum (PMA), as it proposes not only to prioritise border procedures, but also to establish pre-entry control or vetting, with the aim of quickly screening and deciding whether people are to be deported or whether they are profiles in need of protection. They would then move on to the asylum procedure at the border.

None of the procedures are carried out in a gender-sensitive way

The absence of properly trained staff, or the fact that the presence of female staff in interviews with women is still not standard practice, makes it harder to identify gender-specific dynamics that deserve protection.

«It is difficult to identify all the violence experienced, to communicate it to a third party, in many cases a male police officer, in a very hostile environment. It is almost impossible. All this has an impact on the interview and greatly reduces the chances of recognition».

SJM Spain Legal Team

Moreover, both procedures share the following shortcomings:

It is not the right time

The protection interview, which initiates the process, finds the applicant at a time of life that is often not the most convenient for them. The interview requires perfect coherence in the story so as to confirm accuracy, without taking into account that it is not always possible to give a logical account, or to be emotionally prepared to give an adequate, detailed and coherent description of everything they have experienced.

In the case of border procedures, the person does not have adequate information, preparation and accompaniment. The lack of time makes it difficult to internalise and understand what has been experienced, both at origin and during transit.

The interviewer is not the right person

In both procedures, the police carry out the interview. This approach generates an absolutely hierarchical relationship, insofar as it is the same body or institution that conducts the interview and enforces deportation in the event the application for international protection is not accepted for processing.

It is not the right place

A police station is not a safe place and does not create the appropriate circumstances feel calm and face the interview.

In the case of border procedures, the application and processing of international protection is conducted in an area inside the airport where every person who has been prevented from entering is confined, with no discrimination in terms of profile or reasons for detention. In the case of the Southern Border, interviews are conducted in areas close to the border posts, or in the CIE, settings that make it hard to forget the hostility experienced and exacerbate the perception of being in “no man’s land”.

THE EXPERIENCE OF MIGRATED WOMEN IN THE SPANISH STATE AND THE BASQUE COUNTRY

«Being a migrant woman in Spain means double the effort, very little sleep, a lot of responsibilities, a lot of suffering, loneliness, and sometimes silence. Even if you have your own opinion, while you are a migrant, you have very little voice».

Olga Mejía, Honduras

.

It is not the same to be a person living in Spain under the international protection system or in a regular or irregular administrative situation.

Nor is it the same to be a black or Latina woman, as skin colour or language, among others, make a huge difference. Although all women face human rights violations and different forms of violence, women in an irregular administrative situation are more vulnerable and vulnerated. Remaining outside the system and being invisibilised denies them access to existence, registration, census, a roof over their heads and a safe place to live…

The threefold condition of being a woman, a migrant and in an irregular administrative situation complicates the task of escaping the cycles of gender-based violence against women. And if the condition of being black or being a mother is included, then it is practically impossible. As happens at origin and during transit, motherhood has a major impact on arrival and destination. In addition to the obstacles they encounter from Spanish society, the family also exerts pressure. In this regard, motherhood means that women are forced to accept inhumane working conditions. Both in the case of women accompanied by their children, and in sending remittances back home.

I have nephews and nieces. I have a mother and I have grandmothers in my country who I have to support financially. I am not the only one depending on my salary. Although I am not a mother, I am the head of the family.

Silvia Zuñiga, Nicaragua.

Que las mujeres sean quienes sostienen los cuidados de toda una sociedad y los de su propia familia no sólo impacta sus vidas y cuerpos, sino también en la vida de las hijas e hijos que dejan atrás y de esas otras mujeres que se quedan a cargo.

This is how the global caregiving crisis is replicated. The fact that women are the caretakers of an entire society and of their own families has an impact not only on their lives and bodies, but also on the lives of the children they leave behind and of the other women who are left behind to care for them. The vulnerability and instability faced by many women means that their children live in conditions of less security for their lives and development. This has nothing to do with an attitude of lack of protection by the mother, but rather with the spiral of violence and discrimination that the system has generated against the migrant population, and specifically against women.

The continuum of violence in accessing rights

As soon as they set foot on Spanish soil, migrant women find themselves vulnerated and invisibilised insofar as they are not considered citizens.

This invisibility permeates all spheres of life and conditions their ability to avoid situations of institutional, cultural or direct violence.

In terms of the acknowledgement of rights, the Immigration Act (LOEX) divides rights into three blocks:

Those that foreign nationals can access by virtue of the fact they are persons.

01

Those that only persons in a regular administrative situation can access, as they require certain administrative conditions.

02

Those that foreign nationals cannot access.

03

The current reality is that an increasing number of rights fall into the second group, and therefore require a regular administrative situation in order to be asserted. Among others, health, education and accreditation of studies, or access to public housing assistance systems.

According to the Spanish Immigration Act (LOEX), people who are in an irregular administrative situation can access regularisation through employment integration, social integration, family integration or integration for training purposes. With the exception of family integration, the other three require proof of continuous, legal residence in Spain for a minimum period, and in the case of family and social integration, it is also necessary to prove the existence of an employment contract.

La imposibilidad de acceder a una serie de derechos básicos supone la perpetuación de un racismo institucional que expone a la población migrada.

How can a person in an irregular administrative situation prove that they have worked in the State, and how can they be expected to prove continuous residence? In fact, given that access to housing is a widespread problem in Spanish society, how can legal residence be a requirement for people that the system does not recognise? Without a census record, residency or employment contract, no regularisation is possible.

The lack of access to a number of basic rights perpetuates institutional racism, exposing the migrant population, and especially – though not only – those who are in an irregular administrative situation, to constant discrimination and violence. Institutional racism has an impact on the systematic violation of access to two fundamental and priority rights, work and housing. Furthermore, the intersection between the experiences of being a migrant and the specific impact of gender-based violence against women means that institutional racism has a more severe impact on women.

It is pure survival and to be resilient in facing each day […] Our work is to deconstruct the mindset that people have towards migrants, with all the rumours, the stereotypes that migration itself brings with it […] We must be constantly demonstrating and striving.

Marie Lucía Monsheneke, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The informal, invisibilised work environments, the vulnerability and the need for income to which the system confines migrant women to, make an ideal context for exploitation and abuse of all kinds: wage discrimination, debt claims, accident hazards, sexual advances, and other gender-based violence against women.

In addition to economic instability and the difficulty of access to housing, there is also the problem of access to the census. Access to the census for foreigners requires identification documents such as a valid Residence Card or passport. If this is not provided, a census registration authorisation is required, which depends on the willingness of another person, e.g. (an)other person(s) residing at the address or the persons who own the property. These requirements create a relationship of dependence on the “authorising” person. This reality specifically affects women, as the need for a roof over their heads may influence decisions that perpetuate gender-based violence perpetrated by that person.

WITNESS ACCOUNTS

#RESISTANCE

Thanks to the strength and resilience that characterise many women, they manage to develop resistance, coping and survival mechanisms.

Strategies

Hope

Those who are believers thank God for not having died along the way and feel that their faith accompanies and protects them. Another way of creating expectation and hope is the chance to access training, which despite being gender-biased and limited to specific sectors of work, allows them to look forward to a future project.

For those who are mothers, hope is strengthened by imagining a family project. Motherhood is a differentiating and influential element throughout the whole migration process that allows them to find strength in dreaming of reuniting with their children, if they have had to leave them in their country of origin, or in thinking about shaping and offering a better life when they are together.

One of the most important things is to have a life […] Regret… the more you regret, the less you move towards the possibility of a future. Things happen for a reason, everything is an experience. Is it hard? Of course it’s hard… but I don’t know what would have become of me if I had risked going back to my country. Maybe we wouldn’t be chatting now. […] I’m grateful for that, for staying alive.

Matilda Noriega, Guatemala

Community

Community is an essential element in both preventing and overcoming violence. In both contexts, support networks of women or compatriots are recognised as safe spaces for healing. These networks take shape as advice and recommendations, based above all on mutual support for survival. Small communities, which make it possible to build through sisterhood, into (self-)recognition and empathy, which in many cases is crucial to facing similar problems.

Simple examples such as when a mother gives birth, others come in to support her to make the experience easier. Or when they have to leave the shelter and find a place to rent, they look for and organise themselves to find where to go, some work and others take care of the children… Building a community and standing up together is the main strategy for survival and resilience.

Joanna Williams, Kino Initiative.

Social organisations set up along the route, and especially in border zones, offer spaces that promote and accompany women’s circles focused on emotional health, in response to the numerous forms of violence they have suffered. In both Mexico and Morocco, there are women’s support groups addressing the normalisation of sexual violence.

Organisations that offer psychosocial support and/or legal advice are not only acknowledged for their professional accompaniment and as a source of access to information, but also as safe, friendly and trustworthy environments. They are meeting places, where support and solidarity relationships are forged among peers.

When you arrive here (Bilbao), there are many places of welcome or reception, but you have to get to know them so as to establish networks and grow stronger together. Because we women are empowered… We are empowered women!… but there is a lack of opportunities to “push” each other… We create these synergies to walk together and to support each other.

Marie Lucía Monsheneke, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Family and access to resources

Particularly among the sub-Saharan population, who find it harder to access employment, alternatives such as hairdressing, beauty salons, typical food or street vending… are ways of generating resources and surviving. They are “pure creativity” […] “Micro-enterprises within the migrant population are an essential component”. Also, especially in the case of sub-Saharan women, transnational networks are fundamental. Sometimes they have relatives in French-speaking European countries who send them money. In any case, over and above the economic support and the person’s country of origin, family is a fundamental pillar on an emotional level because it represents home.

Access to la regularisation and awareness of rights

Regularisation goes beyond acknowledgement of citizen; it means recognising oneself as a person with rights and it increases awareness of the importance of reporting incidents. This awareness is a symbol of (self-) defence, as it is based on recognising one’s own rights, but also on empathy and solidarity with other women who are going through similar situations.

Breaking down fear, breaking the silence and knowing that as women, with our words, we can do a lot. […] Communicate all those things that make us feel bad, that make us feel violated […] The more we express ourselves, the closer we will be to finding solutions to situations that sometimes I think I am the only one going through, but in fact, many of us are.

Matilda Noriega, Guatemala.

#RECOMMENDATIONS

Consult the detailed recommendations in the report.

A rights-based, feminist, intersectional approach must be adopted in development cooperation policies, migration management policies, policies for protecting migrant women, and policies for integrating migrant populations in destination societies. This requires dialogue with social organisations and the direct, active involvement of migrant and migrated women.

We also recommend that the Spanish government and other authorities involved promote, at European, national, regional and local level:

A foreign cooperation policy that puts lives, and women, at its core

The reality of forced human mobility requires a sustainable solution, which cannot be achieved without cooperation aimed at coherent, coordinated global governance of migratory flows. This must also place the protection of human rights and life above the national security of transit and destination countries, and which applies a transversal gender approach.

01

A migration and asylum policy with a gender and rights-based approach

European and Spanish policies of externalisation and securitisation of borders do not guarantee access to international protection and limit legal, safe channels. We are particularly concerned for women in need of protection, insofar as the obstacles to accessing international protection and the resulting transit along irregular routes are factors that directly affect their vulnerability to gender-based violence against women. It is urgent to respond with a gender and rights-based approach, and to eliminate practices that perpetuate violation of the current regulatory framework.

02

Access to feminist rights

The Spanish state and regional and local governments, where they have jurisdiction, must guarantee access to basic inherent rights for all people, regardless of administrative status or length of residence, paying particular attention to how racism and institutional violence impacts women the hardest.

.

03

RESEARCH:

Sara Diego & Yolanda González

COORDINATION:

Clara Esteban

Irene Ortega

Macarena Romero

Zigor Uribe-Etxebarria

AUDIOVISUAL COORDINATION:

Nacho Esteve y Javier Mielgo

WEB DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT:

Tamara Mentxaka (Sembi Comunicación)

PHOTOS:

Delegación Diocesana de Migración

Josetxo Ordóñez

Sergi Cámara

TRANSLATION:

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

Ca-minando Fronteras, Human Rights Centre Fray Matías de Córdova, Equipo de Reflexión, Investigación y Comunicación (ERIC-Radio Progreso), Ignacio Ellacuria Social Foundation, Entreculturas, Ibero Tijuana, Kino Border Initiative, Migratory Affairs Programme of the Universidad Iberoamericana, Ödos Programme, Red Jesuita con Migrantes Latinoamérica y Caribe, Jesuit Migrant Service – Spain, Jesuit Refugee Service – Ciudad Juárez, among others.

And all the organisations and individuals, especially women, who have shared their experiences, work and knowledge, which were essential in preparing this report.

A project by:

Co-Financed By

This website has been co-financed by the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of La Coordinadora de Organizaciones para el Desarrollo and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.